There is a self-portrait of William Mitchell (1823–1900) in Maryport’s Maritime Museum [1], painted in 1899. Most of Mitchell’s other portraits are rather lacking in life, but he clearly knew himself better than his other subjects: the lower part of his broad face with its long, strong nose is hidden by a bush of white beard and moustache, his forehead by a soft-brimmed black hat, but he has a powerful and rather accusing stare. He arrived in Maryport, from County Down, when he was seventeen, one of many Irish migrants who were fleeing the famine at that time, and found work in the Engine Works of the Maryport & Carlisle Railway, painting the company’s coat-of-arms – its logo – onto the carriages and locomotives. He also started to paint maritime scenes, but he didn’t leave his job (by then he was Foreman Painter) with the M&CR for another twenty years, by which time his paintings had become popular and he was receiving many commissions.

‘Mitchell of Maryport’ is especially well-known for his maritime paintings – ships being built, ships at sea, sailing ships being pulled by a steam-tug, ships wrecked or in the process of being wrecked with their crew and passengers being saved. Portraits and caricatures, Lake District landscapes, Mitchell painted them too, many as commissions – but the maritime paintings are populated with people and animals, who catch the eye and make one laugh. There are men gesticulating, children with hoops, old men leaning against walls and chatting, young men sitting on the edge of the pier, legs dangling over the water as they fish, oblivious to the racket around them. There are gulls, mere hints of white wings and black heads, squabbling over detritus in the water or resting on floating branches.

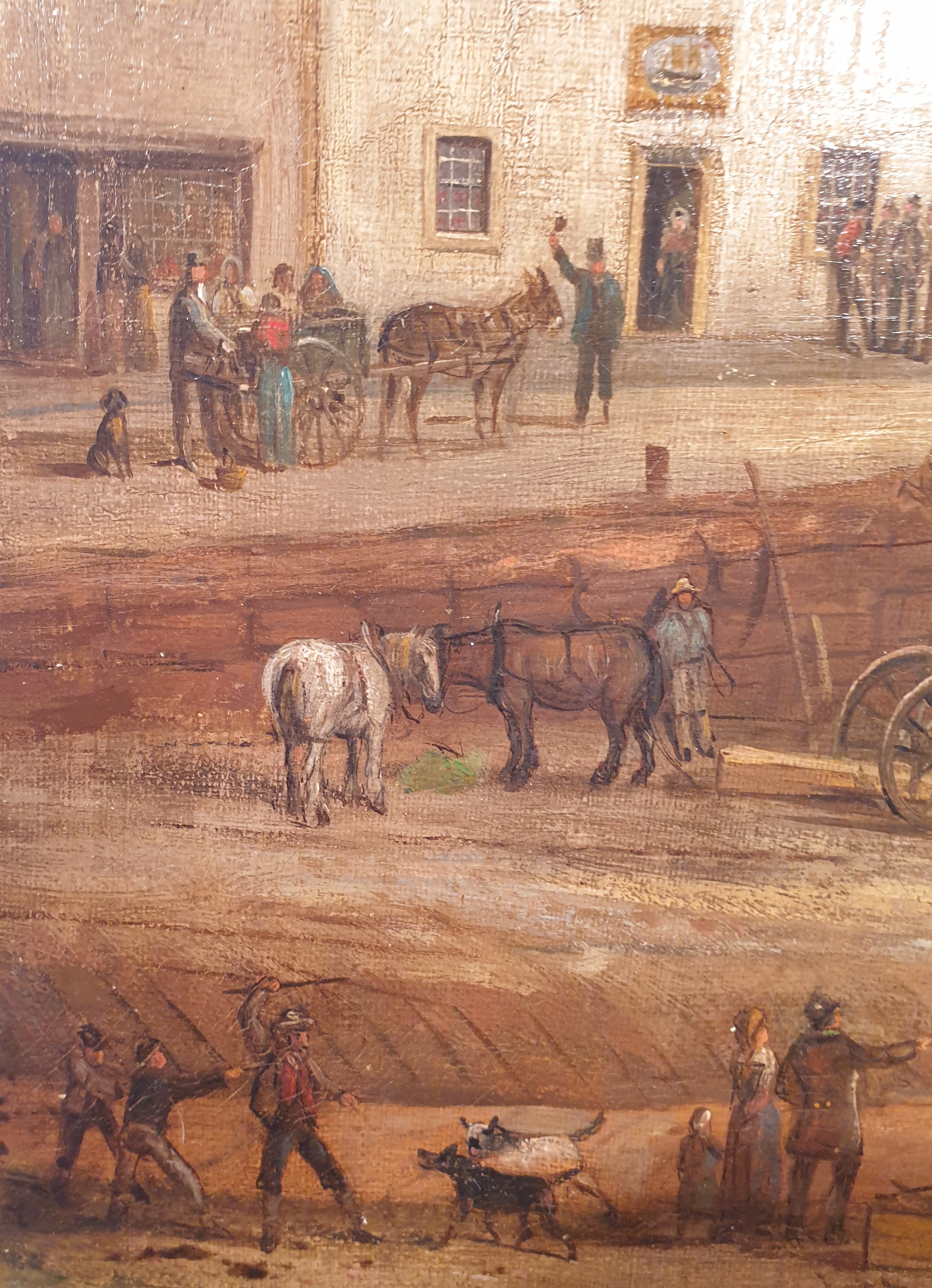

However, it is the domestic mammals that I love most. Two dogs with open, snarling mouths are leaping towards a man who has raised a stick against them; a lad pulls at the man’s arm, trying to stop him. On the road above them, a large furry dog sits impassively watching the drama below. But the same two snarling dogs are in another painting, and this time the boy is missing, the man fights off the animals on his own.

In one of several versions of The Launch of the Collingwood [2] (which Mitchell himself copied from W. Brown – who may have been his mentor), two growling mastiffs are restrained from attacking in each other, their masters pulling them back and trapping them between their knees. Elsewhere, a small cheerful dog prances besides its owner. There are donkeys, pulling carts or patiently waiting between the shafts. There are horses, standing with hanging heads.

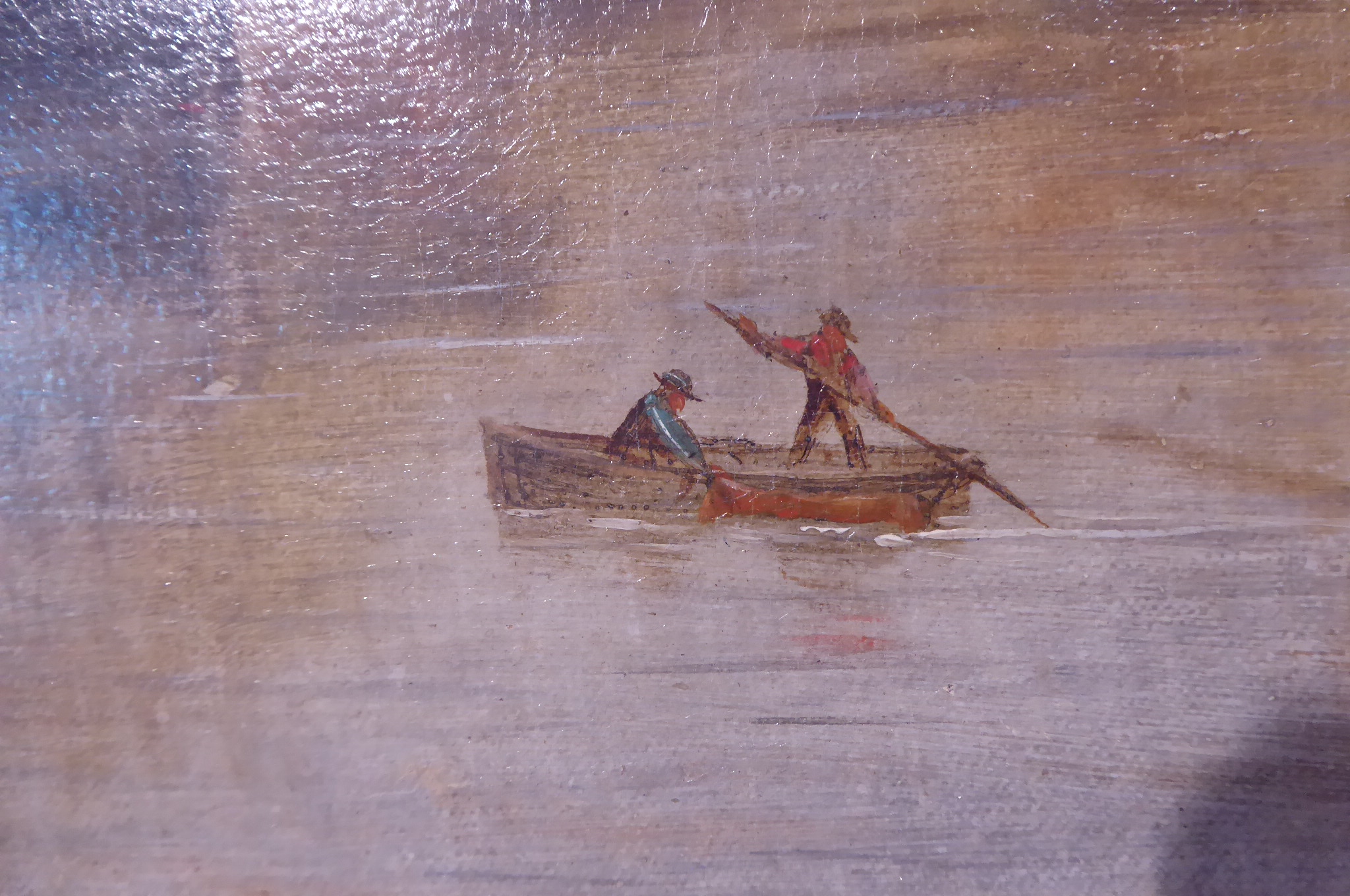

My favourites, though are the cattle. Why are there cattle standing or lying on the slipways? There was a long history of cattle being driven on foot over the shallow waths [3] across the inner Firth like that near Bowness, or across the River Eden, but here in the harbour, it becomes apparent that they have been passengers on a ship. The story is at first hard to unravel – there seems to be a dead cow floating in the water, its legs pointing stiffly at the sky. But a friend of mine pointed out that the gunwhale (the raised side of the ship that acts as a protective barrier) of the ship Gipsy has been lowered, and there are men standing there looking down. The (live) cow has been pushed off the ship – hence the great splash of water surrounding it – and will surely be guided to the slip, for nearby, there is a small skiff alongside which one of the two crew holds another cow as the boat is punted towards the shore. There are two versions of this painting, The Graving Bank, in Maryport’s Shipping Brow Gallery [4]: in one painting the cow has large horns, in the other it has no horns (its head is hard to make out – is it being towed backwards, held by its tail?) And as you would expect, there are many interested onlookers, standing or sitting on the harbour wall – you can almost hear their banter and their laughter. The owner is likely the man standing on the slip and waving his arms. The onshore cattle are unconcerned. My friend suggested that the cattle boat might have come from Ireland, and indeed it is labelled as such by maritime historian David Bridgwater in his interesting blog [5] about the ship-builders of Maryport: “The Brig Gypsy [sic] Discharging Cattle from Ireland onto the Graving Bank. With the Barque Airey ready for the broadside launching in the background in 1837.”

So many of Mitchell’s paintings encourage you to look closely, to enjoy the tiny details, and imagine the unfolding story. Not all his stories are amusing though: some are grim, like the demasted ship wallowing in the stormy sea and, potentially much worse, the wreck of the Danmark in the Atlantic. The passengers, who have been rescued by small, open boats from the SS Missouri, are crammed together, wet and cold and frightened. But at least we know everyone was saved. The description (in the former Maritime Museum) notes that ‘every soul was saved. 735 persons, 65 mere children and under 11 years, 22 mere babies under 11 months’. And above the terrified mothers, a basket containing 4 of the ‘mere babies’ is being swung down to the rescue boat.

Mitchell was born two hundred years ago, and his paintings of ship and ship-building at Maryport give us detailed and intimate views of life in the town in the 19th century. Yet the activities of the people and the animals are not so different from what they would be doing today, and we can unpick and enjoy their stories.

His obituary in the West Cumberland News notes that ‘He was very industrious, and according to the records which he kept, had painted over 10,000 pictures.’ He was also industrious in other ways: he had had three wives and (possibly) at least twenty children, and he was contemplating marrying again just before he died.

Notes:

[1] Maryport Maritime Museum is currently in temporary accommodation at the bottom of Senhouse Street, but will be moving to a specially-designed site in the re-furbished Christ Church in Spring 2024.

[2] Launch of the Collingwood – a version was sold at Bonham’s in 2015; the catalogue notes that “A photograph of the original canvas before it was lined shows an inscription on the reverse that reads as follows: “Launch of the Collingwood” from the/yard. Keswick [sic] Wood Maryport/ This picture copied from the original/ by permission of Wilton Wood Esq./ Painted in 1819 by W. Brown Maryport/and Jenkinson of Liverpool/ W Mitchell Maryport 1884’ ” (Note: the launch date is actually incorrect – it should be 1829)

[3] More on the Solway Waths

[4] The Shipping Brow Gallery opened in November 2023, on the site of the former Maritime Museum, and has a permanent display of several of Mitchell’s paintings (as well as a permanent exhibition of paintings by Percy Kelly, and exhibition space on the ground floor for chosen local artists and the artist-in-residence)

[5] David Bridgwater’s blog about Maryport ship-builders, and more.

[6] It should probably more accurately read ‘ … in his 200th birthday year’!