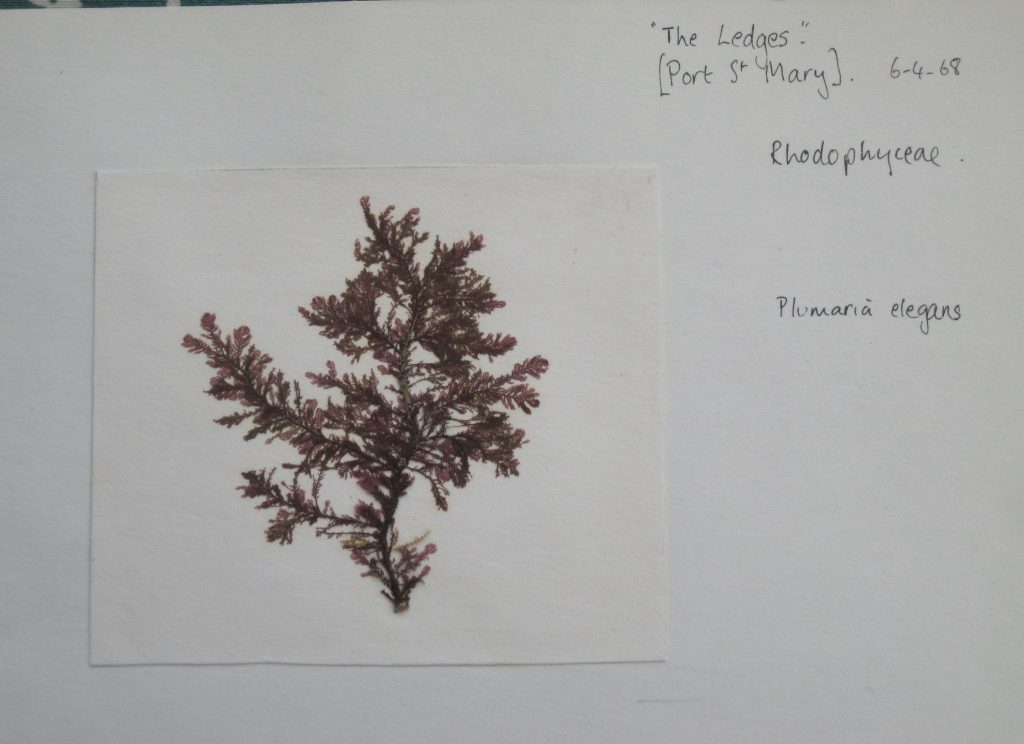

When I was an undergraduate I collected these green and red seaweeds – algae – on a field trip to Liverpool’s former Marine Laboratory at Port Erin, Isle of Man. We were shown how to float the more delicate species onto white card; large sticky molecules of polysaccharides like alginate and carrageenan would be released from the cells, swell as they hydrated, and bind the fronds onto the card as the specimen dried. After all these years the algae have kept their colour and shape. The larger, thicker algae like the brown Fucus species common on rocky shores, were pressed and dried between sheets of newspaper.

Collecting seaweed and displaying it in albums was one of the ‘sea-shore pleasures’ that entertained the Victorian middle classes. Ladies were not expected to be scientific in their collecting but, rather, to arrange their seaweeds in an aesthetically pleasing and artistic manner; the making and displaying of scrapbooks was a parlour pursuit, art rather than science.

(Collecting marine animals – especially sea-anemones or actinia – and keeping them in marine aquaria was another craze, inspired by Philip Henry Gosse’s Actinologia Britannica (1860): so much so that he was to bewail, “They have swept the shore clean as with a besom!”. Gosse’s accurate coloured engravings of actiniae were used by the Blaschkas as a basis for their exquisite glass models: art and science combined – the boundaries were dissolving. You can read more about Gosse and the Blaschkas here, and in my novel Seaside Pleasures.)

Amelia Griffiths (1768-1858), the widow of a clergyman, had become singularly knowledgeable about seaweeds. From her home-base in Torquay she collected along the Cornish, Dorset and Devon coasts. According to Philip Strange’s fascinating blog-post, “she helped male seaweed enthusiasts in producing scholarly studies on the larger and smaller seaweeds, generously giving her knowledge and donating samples.” Amongst the men was the Irish botanist William Henry Harvey (1811-1866) who went on – with Mrs Griffiths’ acknowledged help – to produce his handbook of British Marine Algae, followed later by the 3-volume Phycologia Britannica, illustrated with coloured plates, and published in 1846.

Philip Strange notes that Mrs Griffiths was often helped by her maid Mary Wyatt (1789-1871) – who later ran a shop in Torquay selling shells and other seashore memorabilia to visitors. Wyatt was encouraged by Harvey “to sell books of pressed and named seaweeds to help identification. Supervised by Amelia, she produced the first two volumes of Algae Danmonienses (Seaweeds of Devon) by 1833. Each volume contained 50 species …” The Algae Danmonienses: or dried specimens of Marine Plants, principally collected in Devonshire by Mary Wyatt; carefully named according to Dr. Hooker’s British Flora eventually ran to five volumes, supplemented with some seaweeds from Cornwall.

As an aside here, Philip Henry Gosse must surely have come across the elderly Mrs Griffiths (she lived to the age of 90) during his early sojourns on the Dorset and Devon coasts, during his own expeditions to collect and identify marine animals for his marine aquaria.

This was a time when science, in terms of enquiry, knowledge and new techniques, was advancing quickly. Scientists (‘natural philosophers’) knew of each other and, if they had been appointed members of prestigious establishment institutions such as the Royal Societies of Edinburgh or of London, they were sure to meet and talk and correspond. Ideas and information spread quickly through letters – Gosse could post a letter from London in the morning to the Rev Charles Kingsley, his collaborator in dredging marine animals in Weymouth Bay, and Kingsley might well receive it later that day – and face-to-face meetings.

While William Henry Harvey was working on the accurate representation of British seaweeds through coloured engravings, lengthy papers with postcripts and addenda were being published by the Royal Society on other methods of capturing images, on paper or metal plates that had been made sensitive to light.

William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was developing a method of recording images as negatives on high-quality paper sensitised with a solution of silver iodide, a technique which became known as the ‘Talbotype’ or calotype process. Light pouring through the oriel window at his home, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, famously imprinted an image of the window on the paper (a postcard of the image can be bought in the Abbey’s shop.)

At the same time, the astronomer and chemist John Herschel (1792–1871), who – like many natural philosophers of the time – had wide and eclectic interests, had been testing the effect of the spectrum of light in changing the colours of plant extracts. He presented his findings to the Royal Society in a lengthy paper “On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colours and on Some New Photographic Processes,” on June 16 1842, with a post-script added in August.

He tested the effect of light on extracts of a wide variety of plants such as elder, poppy, iris, French marigold and solution of gum from the guaiacum tree (formerly used in the treatment of gout), and began to home in on the underlying chemistry and the best methods of producing – and fixing – the colour change of the pigments on exposure to sunlight. Herschel moves on apparently seamlessly to experimenting with the effect of chlorine gas and solutions of salts of chlorine, iron, and ammonium, and speculates on the chemical processes involved, including oxidation. Mr Smee’s ‘ferroses quicyanurate of potassium’ meets with great approval, as it produces the admired Prussian Blue on exposure to light. And, as detailed in the lengthy postscript to his 1842 paper, Herschel develops the method for making what he now calls cyanotypes.

Paper, sensitised with a mixture of iron salts, ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferrocyanate, produces a background of ‘beautiful and pure celestial blue’ – Prussian Blue – around the object that was being recorded. Three washings in ‘spring water’ are required to process the image. And he was pleased with ‘the highly superb weather we have lately enjoyed’, which provided an abundance of the necessary sunlight.

In 1799 a daughter, Anna, was born to John and Hester Children. Hester died soon after giving birth and it seems that Anna later “received an unusually scientific education for a woman of her time”. Her father was Keeper of the Department of Zoology at the British Museum from 1837-40, and was also a chemist and an entomologist. He too was a Fellow of the Royal Society and served as its Secretary from 1830-37. Naturally, he knew Fox Talbot and John Herschel; indeed, they were friends who, along with other scientists such as Humphrey Davy, visited his home – with its well-equipped laboratory – in Kent.

In 1825 Anna married John Pelly Atkins, a London merchant, and they moved to Halstead Place, the Atkins’ family home in Sevenoaks, Kent. Atkins too was acquainted with Fox Talbot, and so, through her husband’s and her father’s friends, Anna learnt about calotypes and cyanotypes, the new techniques of photography.

At the same time as William Harvey was being helped by Amelia Griffiths down on the Devonshire coast, Anna Atkins too began recording the variety of British seaweeds, by using Herschel’s photographic technique of ‘blueprinting’ or cyanotyping: she placed pressed algae under glass on paper that had been sensitised with the mixture of soluble iron salts, and exposed them to the sun. After washing in water, the background colour deepened to a uniform ‘celestial blue’, leaving the detailed outline of the algae in grey; washing, then drying, fixed the colour and the image. Since the object was placed directly onto the paper, these were strictly cyanograms.

Between 1841 and 1853, Anna produced the several parts of her Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, each of which contained around 400 images. It must have been a prolonged and labour-intensive work, for which she must surely have had help from the family’s servants, and perhaps also from friends: the collecting, pressing, identifying; the mixing of chemicals in the dark, the coating of paper, arranging of the specimens, waiting for suitable sunlight, and testing exposure times; the fetching of fresh water for washing; and the drying of exposed prints. It is not known how many copies she made but fewer than 20 still survive, all slightly different, and those at the British Library and the New York Public Library have been digitised and made available online. Inside the NYPL’s copy is the hand-written inscription, ‘Sir John F W Herschel, Bart. With Mrs Atkins’ compliments’. It is even possible to download a Kindle version (in shades of grey) from Amazon.

Much of her work after 1853, such as the beautiful Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns, was made in collaboration with her lifelong friend, Anne Dixon (1799-1864), a second cousin of the writer Jane Austen.

The technique of cyanotyping

It’s possible to find many articles about the technique online, but an inspirational yet straight-forward guide to the technique and to various projects is the lovely book by Kim Tillyer, Beginner’s Guide to Cyanotypes (Search Press).

Basically, just two iron-containing chemicals are required: potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. You make them up separately, then mix them and – in dim light – paint the mixture onto or material paper using a soft, broad paintbrush (without a metal ferrule). The paper must be left to dry in the dark; then the object (‘anything that casts a shadow’, as Kim says) or photographic negative is placed on the sensitised paper, preferably under glass to flatten and hold it in place. It’s then exposed to sunlight (or failing that scarce resource, an ultraviolet light) to ‘cure’.

The pale green-yellow of the sensitised paper or material darkens towards blue in the sun, but is unchanged where it is hidden beneath the object. In bright sunlight the image develops within a few minutes but on a duller day it takes longer – and during a longer exposure the sun moves, so the outline of the object becomes fuzzy.

After washing in cold water until any greenish-yellow colour washes out (the startling Prussian Blue colour develops most strongly during washing), the print is hung up to dry.

Kim Tillyer also illustrates other tricks, such as using hydrogen peroxide to enhance the blue, sodium carbonate to bleach it, or soaking the print in tea to give a sepia tint, and more.

The chemistry:

In the first step of the reaction, ferric (Fe III) ions from the soluble ferric ammonium citrate are reduced in a photochemical reaction, by UV in the sunlight, to ferrous (Fe II). In the second stage, these ferrous ions then react in a complex way with the ferric ions in the potassium ferricyanate.

The result is an insoluble, dark blue compound – ferric ferricyanate – or Prussian Blue.

3Fe2+ + 2Fe(CN)63- → Fe3 (Fe(CN)6)2

After exposure, the colour is brought out further by oxidation during washing in tap water (dilute hydrogen peroxide can also be added).

Results

My first attempt several years ago, using leaves and seeds from the garden, worked astonishingly well, and I was thrilled with the colour. But it was either ‘beginner’s luck’, or else the marine algae really are more difficult. Anna Atkins’ detailed and accurate cyanograms are especially impressive because the outlines have such sharp edges and the background colour is uniformly blue.

I am experimenting with different papers and with coated material such as white cotton, with different ways of coating them, with different ways of arranging the algae, and with different washing-times. Careful arrangement of each specimen on the paper with forceps before lowering the glass is tricky – but important.

I’ve learnt that thick seaweeds, even after pressing, may throw shadows that blur the edges. With very delicate algae, or colonial animals like hydroids, the finer details often appear during washing. Some specimens will always be too thick to use, so other techniques (work-in-progress) have to be devised!

Art meets science: different points of view

Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes of marine algae and British ferns are a mixture of artistry and science, which she intended to be used as an aid to identification. Although I’ve formerly helped run marine courses where we identified marine algae and animals, this no longer seems quite so important to me because I’m enjoying exploring this new multifaceted approach: cyanograms, photographs of fresh specimens, pressed and dried specimens, and algae that have been floated onto card and dried. Animal material – skeletons, empty egg-cases, crab shells and more – are important too.

Here, then, is the possibility to play with different ways of recording shape and colour.

And there is also the possibility to gain different perspectives, and to hint at different points of view.