Dog-whelks, Nucella lapillus, were clustered on the mid-shore rocks in late April; singles, twos and threes, they were apparently uninterested in the barnacles beneath their feet, but were there to socialise or, more specifically, to meet partners of the opposite sex and to mate.

Usually on our shore-walks we see only yellowish or white dog-whelks, with the occasional brown-and-white banded variant, so the range of colours in these copulating clusters was surprising.

And the results of their successful matings were obvious: mats of yellow, vase-shaped capsules glued to overhangs and crevices.

A female Nucella might deposit as many as 100 capsules, each of which could contain up to 600 eggs. The embryos which hatch continue to develop inside the capsule – rather than as a free-swimming phase in the plankton – and eventually break out several weeks later as miniature adults. So why isn’t there an undulating swarm of these tiny ‘crawl-aways’? Almost 95% of the eggs are unfertilised and instead act as ‘nurse eggs’ – a kinder way of saying ‘a food source’ – for the developing embryos. Nucella learns its predatory habits at an early age.

It has a big foot but it doesn’t rely on speed to catch its prey; indeed, research suggests that adults rarely move more than about 30 metres during their life (see the very informative page on MarLIN, the Marine Life Information Network, for more details). There’s no need to rush, because their preferred prey species, barnacles and mussels, are sedentary and usually numerous; neither can escape. Barnacles glue themselves to hard surfaces and secrete calcareous plates around their bodies, and mussels, with their two hard calcareous shells (valves) that can be closed tightly for protection, are firmly attached to surfaces by strong byssal threads.

Nucella radula, x400

From Robert Zotolli’s excellent blog about the Barnacle Zone, http://razottoli.wordpress.com/barnacle-zone/

But Nucella has the tools and persistence to break through these armoured defences. In common with many other snail species, it has a long proboscis, which bears the mouth and a ‘file’ of hard sharp teeth, the radula; a secretion of narcotising chemicals completes the assault.

It either uses the ‘gape attack’ method, pressing its proboscis between the mussel’s valves or the barnacle’s plates, then narcotising the prey and rasping at its flesh with the radula, or it bores – it settles down and drills a hole in the shell. Boring is a mixture of mechanical drilling by the radular teeth, and – since calcium carbonate is dissolved by acid – a chemical attack by acidic secretions from an organ in the sole of the foot.

Then, as soon as the armour is breached, the dog whelk secretes digestive enzymes into the body of the prey, and sucks up the resulting ‘soup’. It’s a slow business.

Quoting from the MarLIN page: “Rovero et al. (1999) reported that the ‘gape’ attack method resulted in prey handling time (including inspection, narcotization and ingestion) of 49-51 hrs depending on experience, compared with a handling time of ~ 100 hrs by boring. Morgan (1972) reported that boring could take 3 days to complete.”

The drilled hole is perfectly circular, surrounded by a bevelled edge. And so, when we’re shore-walking in the Mawbray area where mussels are normally abundant, we examine empty mussel shells for signs of that deadly beauty.

Drilled shells (the borings in the two in the bottom right corner have not yet pierced the shell). In shells drilled by Natica, the bevels are much more pronounced.

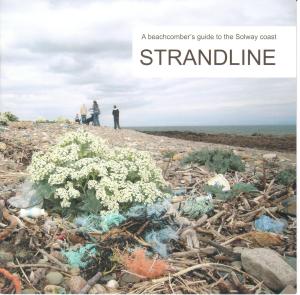

Only very occasionally, here on the English side of the Firth, do we find the drilled shells of other bivalves, such as tellins and Venus. They are much more common on the Scottish side especially at Luce Bay, way out to the West, where Nic Coombey has found shells of the other ‘killer driller’, as he calls it – the necklace shell, Natica. Nic has a fine photo of a Natica amongst drilled bivalve shells on page 10 of his attractive Strandline guide.

Barricane Bay; an engraving by Gosse from his book ‘A naturalist’s rambles on the Devonshire coast’.

My own specimen of Natica doesn’t count as a ‘Solway’ shell – I found it at Barricane Bay in North Devon, on a shell beach that the Victorian naturalist Philip Henry Gosse made famous in ‘A naturalist’s rambles on the Devonshire coast‘. There he was greeted by the female shell-collectors, who offered him ‘the beaded Nerite (Natica monilifera), a large and beautiful shell, to which the local women had given the euphonious appelation of “guggy”.’ He doesn’t mention whether he found drilled bivalves too.