On the first weekend in October the annual ‘Keswick’ Show and Sale of Herdwick sheep is held in Mitchell’s Livestock Mart in Cockermouth. Our tup ‘Bonzo’ had been accepted for official registration in the breed’s Stock Book: his appearance – his grey fleece, and hairy white face, testicles and legs – and therefore presumably his genes, were judged acceptable for sale, and he was being primped for the show. A friend who is a well-known Herdwick breeder came round with a tub of raddle and set to, rubbing the greasy red mixture into the fleece on Bonzo’s back. But up at the mart, surrounded by pens of feisty red-dressed tups who were clashing heads at every opportunity, our tup seemed unimpressed and lay down in his allotted pen, looking bored. When his turn came to show off his masculinity in the ring, his laid-back attitude even prompted some laughter. He did not sell.

Amongst Herdwick breeders, this tradition of dressing the fleece with red raddle is thought to mimic the natural red colour that the sheep would have acquired if they had been grazing on fellsides where the red iron-bearing ore, haematite, was found. These days the pots of raddle are usually bought from Relph’s farm supplies near Penrith.

This red haematite is the same pigment that has been used from as long ago as Stone Age cave paintings [7]; it is used to colour lime plaster and mortar, as ‘Venetian Red’ (see blogpost ‘Hot mix’); and has been used at the Florence Arts Centre (which is on the site of the former Florence haematite mine) as a pigment for modern projects on painting and dyeing. It defines the molehills on the soil above the Triassic Sandstone of St Bees, and the mud on the tracks around the limestone areas of Egremont and Millom, and it smears down the Nab Gill fellside over the pink granite of Eskdale.

In this form, the particles of haematite are small and powdery, mixed in with the soil; it is the least pure form of the ore and scarcely worth working. But the soluble iron salts also once dribbled and trickled through the joints and faults of the limestones of West and South Cumbria, becoming oxidised and insoluble as they crystallised to form veins and lumpy masses of haematite, in sufficient quantities of good quality ore that it was worth mining and smelting it to form iron. This haematite, plus local limestone, and plentiful coal from the West Cumbrian coalfields combined to form perfect conditions for smelting and steel-making, and thereby making Victorian and early 20th century Cumberland rich, with the extra benefits of stimulating improved infrastructure in the form of new railways (for example, the Solway Junction Railway and its viaduct across the Solway Firth [1] ) and improved ports.

Along a gated track close to a quarry a few miles North of the former haematite mines of Hodbarrow and the ironworks of Millom, is the Millom Rock Park. Quarry companies have very large machines for obtaining and lifting chunks of rock, and here the owners have laid out a demonstration of the kinds of rock that are found in Cumbria, such as granite, Skiddaw slate, and andesite from the Borrowdale Volcanics group. The park – a flattened area otherwise cleared of stone – looks a little tired, the ‘type specimens’ no longer identified except by rotting wooden posts from which the labels have vanished, but at one end there is a perspex box inside which is cemented a hefty, bulbous lump of kidney haematite, brought here from Hodbarrow. The information board, headed ‘Millom, Mining and Money’, is still intact and shows a black-and-white photo of helmeted men smiling for the photographer and pushing a wheeled metal truck that is laden with ore; in colour, red would have predominated.

Mervyn Dodd, in his book, The Story of Iron Ore Mining in West Cumbria [2], describes how the different forms of the ore arise: veins are steep and narrow bodies of ore close to faults; flats, as their name suggests, follow the layers of rock; and there are vugs, which are spaces within the rock where irregular shapes like the kidney ore can grow. Some of the kidney shapes can grow to a massive size, like the one from Hodbarrow, and smaller versions were often seen being used as doorstops in the mining areas.

Dodd’s book also has a diagrammatic map that shows the principal areas of the West Cumbrian limestone where haematite was mined, and he includes details of short walks to explore these sites. “Castles in the red ore made/ Are buttressed, tunnelled, turreted” [3] : these mines, in the Cleator Moor and Egremont area and down to the South around Furness, “became the richest mining areas in the world”, according to Albyn Austin [4], but after they ceased being worked, the mines were filled in or cleared, and very little remains to be seen. So my first ‘geological’ outing to a haematite mine was not to a disused mine in the limestone area, but to Nab Gill, one of the mines of Eskdale [4] , in the granite at the edge of the Western Fells.

The twisting road along the dale runs next to the Ravenglass-Eskdale railway line, a narrow-gauge line built originally to transport the haematite down to the coast, but now used by the very popular La’al Ratty engine and its coaches to carry visitors to Boot and back. I drive there on a summer day in June 2021 but it is raining at Boot, the clouds down almost to valley level, so that David and I, each of us hooded and bent against the rain, initially have trouble recognising each other. David Kelly is a retired teacher and former President of the Cumberland Geological Society, and he and I had first met more than a decade previously when he showed me the Triassic Sandstone, dolomite and breccia of St Bees’ Head [5]. When I look back at those notes, I see that he strode ahead effortlessly up the cliff path and, as we waded through sodden vegetation the bottoms of his jeans, like mine, were soon dark and soaked with water. Nothing had changed (except that today I wore waterproof trousers) as I scrambled to keep up with him up the steep path and rubble at the side of Nab Gill!

But first we stop to look at the remains of the platform and loading bay, now almost hidden by bracken, gorse and nettles, where formerly the railway trucks were loaded with the ore. The walls of the building that had contained the office still remain, although the roof is long gone; lichens and thick moss have colonised the mortar and blocky stones of pinkish granite typical of the area.

A straight and narrow track stretches up the fellside behind the building, raised on a base of stones – this was the tramway, an inclined plane, down which the ore-laden wagons would have travelled to the station and been pulled up, empty, to the top.

It is long and almost shockingly steep, and the enormous effort required to move and man-handle the stones and soil into place is almost unimaginable. We stand on its grassy surface and as we look down we speculate about the kind of winch and brakes that would have been needed to control the wagons’ descent.

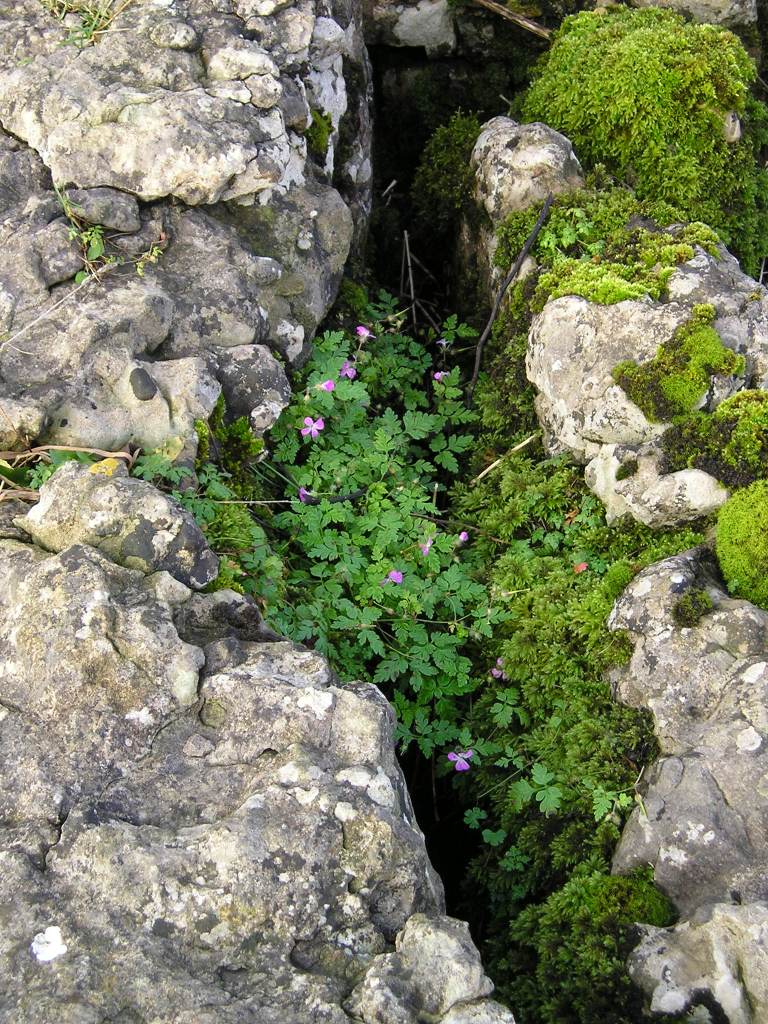

The haematite workings at Nab Gill were in five levels, connected by shafts, and followed a vein of ore that trended North-North-West, presumably along the same fault-line eroded by the gill and along which the iron-rich fluids must once have trickled. The gill, a deep and heavily-vegetated cleft in the hillside, no longer flows with water, probably because it has been considerably altered by the mining operations which started in about 1870 and finally ended in 1917. The slippery path up the cleft has been cleared in places, perhaps by other geologists, and David pauses to show me a small round rock that has been brecciated – it formed by the granite splitting and iron salts infiltrating, so that the fragments of pinkish granite became cemented together with a dark purple glue of haematite. Wherever the soil is exposed, it is red and crumbly.

Although the entries to the levels are still visible, they have collapsed or been filled in, blocked with stony debris, brambles and ferns. Level No. 5 is the lowest, there is little to see at the mouths of No. 4 and No. 3, but by the entrance to Level No.2 David suggests I climb up to look at a boulder.

And here is a vein of haematite, in shining blue-ish-purple bands of kidney ore! It is so unexpected, and so beautiful: the crystals’ upper, smooth convex surfaces seem to bubble out of the rock. They are perhaps a centimetre in diameter and, seen from the side, are conical, sharp-pointed at the other end, the facets of their sides glinting in the grey light. Later, on our descent below Level No.1, we hunt on the scree for samples; the pocket of my jacket still holds a small piece of kidney ore, a smooth talisman to rub between finger and thumb as I walk.

We reach the top of the gill in the drizzle; the climbing has been warm and steamy work, and the grasses are sodden, beaded with droplets of water. Here, adjacent to Level No. 1, is a deep, narrow cavity, an open stope, now protected by a new post and wire fence. We peer down into its ferny darkness, and David shows where a miner would have stood, legs braced each side of the fault as he hacked out the ore. There are also open-cast mines to the North on the top of the hill but they are overgrown, so we don’t bother to explore further.

The rain eases; the clouds come and go, hanging in the dales and on the tops, dropping and lifting, parting in snatches – the views always changing, the distant fells of Langdale being revealed then hidden again. There was formerly a branch line to mines at the opposite side of the Esk; David points out the route. With the end of the rain comes the end of silence, and suddenly there is birdsong below us – the songs of thrushes and blackbirds, echoing in the valley, and the conversations of rooks amongst the trees.

We slither back down the path, picking our way past the Levels, hunting for treasure among the scree. Red earth spills down from the bottom of the talus, and it’s easy to imagine the raddle colouring a Herdwick’s fleece. Four walkers, hot in their waterproofs, huff up the path towards us, pushing on their walking-poles, surprised at the steepness; they have mistaken their route, but are interested to learn about the mine.

I wonder about the person who first discovered traces of ore here – was he (it was extremely unlikely to have been a woman) looking purposefully, or was it serendipity? Did he mention his discovery to someone else, or was he sufficiently well-informed that he knew what he had found? Why, indeed, search amongst the granite, when most haematite discoveries were in the limestone or even sandstone? I think about working in these conditions, the ‘commute to work’ as we would call it these days: climbing the steep path, carrying heavy tools; the changeable Cumbrian weather; the dark, enclosed spaces inside the mines; the dangers of rock falls, and of the speeding, laden wagons on the tramway …

The history of the Eskdale mines makes interesting reading. As with all mining ventures, the fortunes of the owners, and of course the workforce and their families, depend on geology – the size and quality of the veins of ore or coal – and the market value. Two great variables, one of which was set millions of years previously, and the other of which is man-made and subject to even daily variation. The Eskdale mines, as Austin [4] writes, ‘were hopelessly uneconomic’ and were finally closed in the early 20th century. Nothing remains of the original railways, except the re-built track, from Ravenglass to Boot, for La’al Ratty. As we walk back to our cars, the valley reverberates with the repeated hooting of the little train, and soon dozens of people, single and in families, with buggies, rucksacs and trekking-poles, are walking out of the station and along the road to Boot.

Where does the haematite come from?

Iron itself is very reactive with oxygen and water, being oxidised to form ferrous (Fe2+ or Fe (II)) oxide, or ferric (Fe3+ or Fe(III)) oxides (like ‘rust’); interacting with water to form ferrous hydroxide; or with sulphur to form iron pyrites, otherwise known as ‘fool’s gold’; and so on. The enormous deposits of haematite that lay in the limestone and granite of West Cumbria are made of insoluble ferric oxide.

So what was the source of these enormous quantities of oxidised iron? Iron is one of the most abundant elements on earth, and it’s thought that most of the iron in the oceans has entered as dust from deserts, or via rivers and estuaries, or – in the early oceans – from eruptions of volcanic ridges on the sea-bed. (While I was writing this, the Fagradalsfjall volcano system in Iceland has been erupting for six months, pouring out vast quantities of lava which, in the case of this volcano, originate from the iron-rich mantle rather than the overlying crust; at that time there was a possibility that the lava from this shield volcano might eventually reach the sea.) In those early seas there was little oxygen, so the iron that leached from the basaltic lava was primarily in the soluble, reactive ferrous state. But with the evolution of bacteria that could use the sun’s energy to photosynthesise, the oxygen levels rose dramatically, and the iron in the ferrous state was oxidised to form insoluble ferric oxyhydroxides, which precipitated – and were available to be further oxidised to form compounds such as haematite.

The next question is, why is there such a concentration of haematite in West Cumbria? There are various theories (of course – and it’s impossible to set up the experiment to check them out), but one of the ideas relies on the fact that the magnetic North pole has wandered around over the tens of millennia of years, and on the other convenient fact that haematite is weakly magnetic and retains the ‘memory’ of where the magnetic North was when the ore was deposited. Measurements have shown that the deposits of haematite laid down in the eastern margins of the existing Irish Sea – in other words, in West Cumbria – all hold roughly the same memory of these ‘palaeopoles’. Or, as Crowley and collaborators write [6], “Correlation of poles with the European apparent polar wander path indicates that these ore deposits formed during the Middle Triassic”, in other words between 247 and 237 million years ago – after the end of the great Permian extinction, and before flowering plants evolved. In their paper they speculate on the development of ore-forming fluids within the evolving East Irish Sea Basin, “and subsequent migration of fluids to basin margins where iron was precipitated as hematite.” Where the ‘fluids’ came from and how they were oxidised to ferric oxide can only be guessed at, but was probably not due entirely to the metabolic activity of biological organisms.

So, those fluids crept and trickled their way into the permeable sandstone, and through to the limestones that originated from the skeletons of marine organisms in earlier warm seas, and into the joints and faults in the hard pink granite – eventually becoming a valuable commodity as humans discovered the usefulness of iron.

Notes:

This blogpost is part of my ‘limestone lockdown’ project. For an Introduction to the project, and a guide to the list of related posts, see Limestone in the Lake District: an Introduction – and the ‘categories’ list in the right-hand bar.

[1] Crossing the Moss. The Solway Junction Railway and Solway Viaduct

[2] Mervyn Dodd (2010) The Story of Iron Ore Mining in West Cumbria (Cumberland Geological Society; ISBN978-0-9558453-1-4

[3] Norman Nicholson (1944), lines from the poem Egremont, in the collection Five Rivers 1944

[4] Albyn Austin (1990) The Mines of Eskdale, on the Industrial History of Cumbria website

[5] See Chapter 6, ‘Red’, in The Fresh and the Salt, the Story of the Solway (2020) Birlinn Books

[6] Stephen F. Crowley, John D. A. Piper, Turki Bamarouf and Andrew P. Roberts (2013) Palaeomagnetic evidence for the age of the Cumbrian and Manx hematite ore deposits: implications for the origin of hematite mineralization at the margins of the East Irish Sea Basin, UK. Journal of the Geological Society, 171, 49-64

[7] There’s an interesting podcast about ‘Ochre’ – its origins and uses – in the Chemistry World series