“At Rockcliffe [Marsh] it’s about the birds, it’s about the saltmarsh as a vegetation community; it’s about the geological interest in the development of saltmarshes. Many other saltmarshes have been enclosed and changed because of agricultural methods, but the Solway marshes haven’t suffered to the same extent.” Bart Donato

Giles Mounsey-Heysham, the owner of Castletown Estate and Rockcliffe Marsh, refers to Bart Donato as the Estate’s “guru from Natural England” (NE), which made Bart laugh when we met in a café near Kendal in August 2017, but it was immediately obvious that he was very enthusiastic about his involvement with Rockcliffe.

He explained, “The Marsh has been part of an agricultural system for a thousand years or so – it’s not wild, it’s not a natural marsh, but a by-product of the agricultural system set on a natual landform. Local farming systems were once dictated by local needs, but over time have become subsumed within agri-business on a global scale – we have to try to buffer the system.”

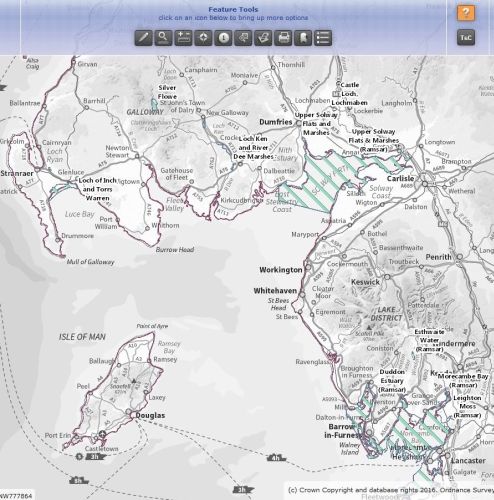

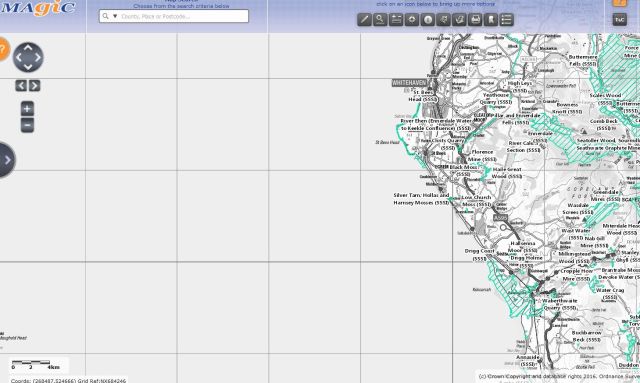

Giles had asked for his help back in 2004 because “the grazing régime wasn’t working.” The result was that the Marsh was put into the Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) scheme, with funding for managing the saltmarsh better for birds. The rôle of NE is look at and secure Rockcliffe’s SSSI designation. “We look at the natural heritage, and think what’s the right management to look after that asset,” Bart explained. “We have to look at the flora and fauna and work out what’s best to support them. As for birds, it’s not just the breeding waders but also the wintering populations, the really big flocks of barnacle geese.”

Managing the grazing

“We don’t have the magic grazing system [for the birds],” Bart acknowledged. “We probably never will because the market drives things like the time and the type of grazing stock.” Geese “like a bowling green” but breeding waders prefer rougher vegetation, so the challenge is to balance this, to manage the grass growth to provide a mosaic. “We’re bringing the Marsh back to something more goose-y and breeding-wader-y.”

I imagined the long, muscular tongues of cattle, ripping off the grass, and the crisp snipping by sheep. That year the Marsh was also a temporary home for a herd of gypsy horses, black- and brown-and-white, and Bart said he “was quite excited to see them – they take on the rougher vegetation like tufted hair-grass, they take it down, and they behave very differently from the other stock.”

In the winter, most of the sheep and cattle are taken off. “The Marsh needs to be grazed enough to stop it growing, yet to keep a bit on it until the geese come again,” Bart said. “The winter grazing is problematic because of the marsh’s great size, the creeks and the winter tides.” Ultimately, “The tides are in control – creeks become quagmires, the pens get churned up.”

Total inundation of the Marsh also, as might be expected, has dramatic effects. For many years Mike Carrier was Honorary Warden for Cumbria Wildlife Trust’s involvement with the Marsh, and in his report for the period 2006/2015 for NE and the Trust, he wrote: “Both tides and weather play an extremely important role in the everyday life of Rockcliffe Marsh. Complete tidal inundations of the whole marsh occur perhaps no more than two or three times per year … When they do occur, the effect is to leave parts of the marsh under water for days particularly in the winter when little or no evaporation or natural drying out takes place. Should complete inundations take place during the [bird] breeding season, the effects can be catastrophic.”

Anatomising the Marsh

Bart talked about the need to manage the grassland as a mosaic of ‘bowling green’ and tufts and longer vegetation, to encourage breeding and grazing birds. But the HLS scheme was also about managing Rockcliffe as a saltmarsh, a mosaic of wet ground and creeks and open water amongst the vegetation, “a Swiss-cheese effect of water-bodies and big sheets of water.”

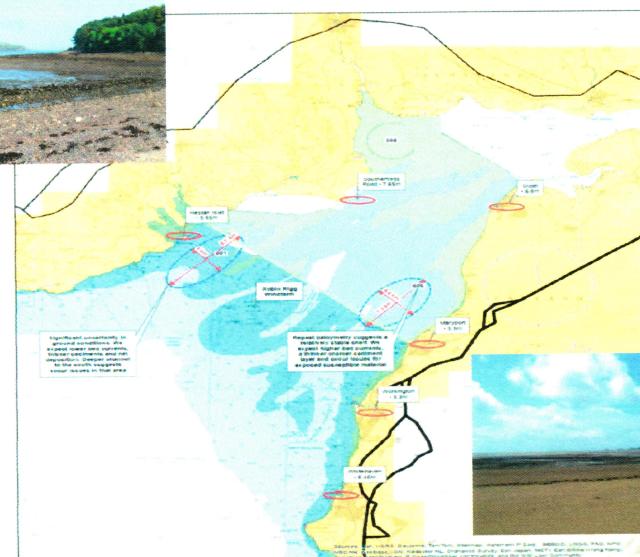

To do this, it was important to understand how the saltmarsh forms and develops. Rockcliffe isn’t only growing outwards, it’s growing upwards too. At the edges, ‘pioneer’ plants like Pulcinellia grass, Salicornia (samphire) and, as at RSPB Campfield further down the coast, the alien grass species Spartina, establish a root-hold. The meshwork of roots stabilises the trapped silt and forms a tiny island. Small changes in water-currents cause more sediment to be deposited and the islands fuse. Sediment accretion raises the level of the new-formed ‘land’, plants colonise, more sediment is trapped … and so a terrace is built up and the diversity of plants increases.

The Solway Firth has famously sediment-laden tides, the sea often the colour of milk-chocolate during strong winds. When the incoming tide reaches the head of the Firth at Rockcliffe and meets the outflowing freshwater of the rivers, it deposits its load of silt. Moreover, during storms, sediment also washes down the rivers “from everybody’s fields”, Bart said, and much of this gets trapped upstream of the ‘neck’ of the Firth at Bowness, so that above-average amounts of riverine sediment are deposited too.

Upward growth, though, is caused by ‘topping tides’, the high Spring tides that happen when the Moon and Sun are in alignment and their gravitational pull is greatest. Then, the water, “brown with muck”, creeps in through the creeks and overspills onto the Marsh. The vegetation creates at its base a layer of still water from which the sediment precipitates out. On a big tide, there’s a relatively long period of slack water at the head of the Firth, which means a longer period for sedimentation to happen; as much as 1cm of silt might then be deposited within a few tidal cycles amongst the grass and herbiage. When Giles had given me a tour of the Marsh he had jumped off the quad near the elbow of the Esk, next to a line of fence posts. “They’re gradually getting buried,” he says, lifting his hand to indicate they were nearly one-third higher when knocked in.

The sediment deposition affects the creeks and pool formation too. In the café, Bart got out the PlayDough, and fashioned a blue creek in a purple Marsh to illustrate what happens. When an incoming tide overtops the banks and spills onto the Marsh, the vegetation traps sediment close to the creek, so that levées gradually form along the banks. As the tide drops, the water on the Marsh cannot escape and forms ephemeral pools, stretches of open water, which slowly decrease by evaporation.

A breached levee means the water drains away, back into the creek

When the levee is intact, overtopping water remains as pools

But at one stage in the marsh’s earlier management for sheep, drainage ditches were dug and the levées breached so that the standing water could drain back into the creeks. Now, under NE’s management, the drains have been blocked, the gaps in the banks filled and wet flashes have been dug for waders. The hydrology of the Marsh is being restored to its former state.

(Note: there is much more about other marshes and merses of the Solway, and specifically also about Rockcliffe Marsh in my book The Fresh and the Salt: the Story of the Solway; Birlinn, 2020; see https://thefreshandthesalt.co.uk/chapter-four/ )