We went to the Scottish side of the Solway Firth to hunt for a boring mollusc.

Or, rather more accurately, for the empty shells of a marine snail, Natica monilifera, known variously as the Necklace Shell, the beaded Nerite, or even – according to Victorian naturalist Philip Henry Gosse, as ‘guggy’.

In 1854 Gosse made his second attempt (the first had been foiled by bad weather) to reach Barricane Bay on the Devon coast. In A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast, he writes that Barricane’s “peculiarity is, that it has a beach entirely composed of shells … From the grassy slope at the top of the cliffs a narrow footpath leads steeply down to an area of what seems to be small pebbles; but which, on examination, prove to be shells, of many kinds. Groups of women from the neighbouring hamlets may always be seen, during the summer months, raking with their fingers among the fragments, for unbroken specimens; collections of which they offer for sale to visitors.”

Many years ago, I too went to Barricane, helping to take a group of Cambridge University students on a marine ecology class, and we too spent much of the afternoon lying and sitting on the shore, ‘raking with our fingers’.

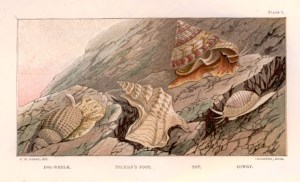

Gosse recounts that “Besides two or three little kinds of whelk, and the common murex and purpura, which are everywhere abundant, and the beautiful little cowry, which cannot be considered rare, there is the elegant wentle-trap (Scalaria communis), the elephant’s tusk or horn-shell (Dentalium entalis), the cylindrical dipper (Bulla cylindracea), called by the local collectors ‘maggot’, and the beaded Nerite (Natica monilifera) a large and beautiful shell, to which the local women had given the euphonious appelation of ‘guggy’.”

We found all of those, and more: I still have most of my collection, of 37 different species, including cowries, Dentalium, Bulla, the beautiful wentletrap Clathrus (Scalaria) and a perfect specimen of the predatory Necklace Shell, Natica.

As I mention elsewhere, Natica bores and dissolves a neat hole through the shell of its bivalve prey – and although we sometimes find bored bivalves such as tellins on our southern shore of the Solway, we have not found Natica. But I knew from Nic Coombey that Natica could be found across the Solway at Luce Bay (sheltered by the Mull of Galloway so, strictly, on the Irish Sea), so we went there for our ‘guggy hunt’.

The shells on the sandy western stretch of the great bay are well-sorted by shape and size. The first search showed only cockles and razor-shells; then there were cockles and other small bivalves – only a very few of the bivalves showed the bevelled bore-hole characteristic of Natica’s activity. But then I came to an area of a few square metres where Natica shells had been cached by the tide.

They were mostly small and faded – but there they were!

Gosse, a consummate shore-walker, collector and teacher, writes with eloquence and enthusiasm about the biology of the species – their mode of predation, the ‘necklace’ or curved gelatinous band of eggs they produce, and their movement – in his Natural History of the Mollusca. (Gosse, too, was the ‘inventor’ of the marine aquarium, which he frequently used to help him observe an animal’s behaviour.) “When put into an aquarium with a sandy bottom, they soon begin to crawl just beneath the surface of the sand, their foot alone being immersed in it … The progress of the creature through the fine, soft sand, is very curious to witness.” Presumably this sub-surface ploughing enables the snail to find its buried bivalve prey and set to work drilling with the radula on its proboscis, “its augur or spiniferous tongue”.

It might seem ridiculous to be happy about finding a few empty shells – but I really was!

‘Canoes’

Then, a surprise find made me even happier. At first I thought this large shell must be foreign, discarded from someone’s collection. But then I found more specimens: they looked like very large versions of the Bubble Shell, Bulla, that we had found at Barricane.

My copy of Nora McMillan’s British Shells (bought in 1975) refers to it as Tricla, but that name is no longer recognised: the animal is Scaphander lignarius, the Canoe Shell.

It isn’t often found, but interestingly a Google search turned up a blog by Valerie Harrison who lives on the Rhinns of Mull in Galloway, and has found Scaphander shells in Luce Bay on two occasions, the last in September 2012.

Scaphander isn’t a borer but it’s highly predatory. Paul Chambers, in his book British Seashells: A Guide for Collectors and Beachcombers, writes that the animal “has astounded scientists with its display of gluttony on the sea-shore” and Gosse, in Natural History of the Mollusca, says “they are very voracious and sometimes swallow bivalves so large as quite to distort their own form”!

I collected a few more shells, in the soft light and long shadows of a late-April evening. The wind was bitterly cold (it would snow the next day) – but it had been a very good evening on the shore.