From the hill at Watchtree Nature Reserve you can look across to the upper reaches of the Solway Firth, the Borders and, to the East, the Northern Fells. It’s early February and the snow-coated top of Skiddaw is glistening in the sun; a skylark is singing, and the clutter of tree-sparrows squabbling in a hedge are momentarily silenced as a sparrowhawk sweeps through.

Frank Mawby, a Director of the Reserve’s Trust (and former Reserves Manager for Natural England in this area) drives along the runway to meet me; he has been organising the volunteer work-party. He tells me he’d like to get some funding to build a tree-top hide ‘so that people can see where we are in relation to the Firth.’

Ideas and plans and optimism about the future – these have always characterised the development of Watchtree, right from its inception. I came here in 2011, on the tenth anniversary of the Foot-and-Mouth (FMD) epidemic that swept through Cumbria and now, on the fifteenth anniversary, I have come back again to see how the Nature Reserve has progressed since then.

Watchtree is on the site of one of the Solway’s several wartime airfields, Great Orton, which, abandoned after the War, became an unofficial ‘community resource’ used by microlite flyers, clay-pigeon shooters and youngsters learning to drive.

But then, in February 2001, it was commandeered as a mass grave, an enormous engineering and logistical feat that saw 26 burial ‘cells’ dug – and filled. The name, Great Orton, became synonymous with ‘the killing field’, the great trauma of the county, which many find hard to talk about even today.

There is a plaque at the gate, mounted on a piece of Criffel granite, a glacial erratic that was dug up nearby:

“A Symbol. To the birth of Watchtree Nature Reserve, dedicated this day the 7th May 2003, the second anniversary of the final burial.

A Memorial. To 448,508 sheep, 12,085 cattle, 5,719 pigs buried here during the Foot and Mouth outbreak of 2001″

Half-a-million animals; so few infected. This is not the time or place to dwell on the impact of the disease, but you can read a fictional account (based on fact) of what happened to Madeleine, a Herdwick sheep-farmer, in this extract (page 20, Firecrane) from my novel, The Embalmer’s Book of Recipes.

But now, one can almost forget what lies beneath the wildflower meadows, the woods and the lagoons.

Next to a hide overlooking a pond, Frank opens a wooden door in a fence (this requires some spectacular contortions as the clasp is on the far side) and takes me into a grassy, scrubby, wetland area by the four lagoons. These lagoons are ‘operational’ and not open to the public; the richness of the surroundings is breath-taking even at this wintry time of year – the common reed Phragmites and bulrushes Typha latifolia fringe the water; the leaves of yellow flag and golden-cup are starting to show at the edges. A teal takes off, and then three snipe, zig-zagging with flickering wing-beats. Willow and birch are growing along the sloping banks, and Frank shows me how they are coppiced on different sides each year. There is gorse, too – as always, some of it in flower (‘When the gorse is not in flower, then kissing’s not in season‘).

The still water reflects the blue sky and slowly-moving clouds. ‘It’s very clean water, and biologically it’s got an awful lot growing in it,’ Frank tells me. ‘We get Great Crested Newts, tadpoles, dragonfly and damselfly nymphs. And Great Diving Beetles – though they’re mainly in the main lake. They’re voracious predators, they’ll even clean out the tadpoles.’

As for the birds that have been seen around the lagoons, ‘We’ve had sedge- and reed-warblers – they were a surprise. Six or eight pairs of linnets, goldfinches, willow warblers – and the usual dunnock, wren, robin. Coot, moorhen, Little Grebe. Reed bunting. White-throat. And swallows love it here, feeding over the surface.’

To understand why there are wetlands and lagoons here, on a former airfield, you have to understand what happened during 2001. If you stand by the gate and look along the western runway it’s impossible to ignore what lies underground. There are regularly-spaced green metal boxes and metal cowls and the ends of pipes. Part-hidden in the wood at the northern end are the buildings, with humming machinery and computerised read-outs from the biodigester plant where the contaminated liquid from the burial cells is processed. ‘Leachate’ became part of our common vocabulary for several years after FMD; one estimate is that it could take 40-60 years to disappear.

‘The whole site is very complicated,’ Frank had explained to me in 2011. ‘We have to consult Interserve [the company contracted to oversee the drainage] and look at all the plans, especially when we’re digging ponds. There’s masses of electrical wiring as well as the drainage schemes.’ The whole burial area is lined by a wall of bentonite, a mix of clay and slurry that is 12 metres deep and pressure-driven into the bed-rock. There is a ring-drain within each cell, and leachate is pumped out of the cells to the biodigester where bacteria break it down. Drainage of the whole site is indeed complicated, in that surface water (from rain) is collected into ditches, where it joins with the deep ground-water and treated effluent, and is sent to the lagoons and reed-beds for the sediment to settle and excess nitrogen to be taken up and removed. ‘We’re at the top of a hill, so any water coming off must be absolutely pure – it’s tested at all stages, for ammonia, solids and pH.’

And also back in 2011, Frank had told me, ‘Although the waterbodies were created by us, everything in them is developing naturally, reeds are coming in and we should soon get reed-buntings. The Great-crested Newts wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for us. And they’re going further afield, spreading and spreading every year.”

Now, five years on, the reed-beds are flourishing, and he can reel off the number of bird species and say, ‘It’s an amazing bird list!’

Nest-boxes, and bird-feeders with seeds and nuts, hang from some of the trees: ‘The tree-sparrows are doing well. They’ll clear out one of those feeders in a day. Visitors get a lot of pleasure seeing the birds’. We see a yellowhammer on a bird-feeder, and I remember that there had been hopes that they would breed on the Reserve. ‘They’re not yet breeding here – but the hedgerows are about right for them now, so hopefully we’ll see some nesting this year.’ And although the sandmartins are still resisting the invitation to nest in the artificial bank that was built for them, oyster-catchers nested on top of the bank instead.

What is Frank most pleased about? ‘Ah,’ he pauses and considers. ‘All things are doing reasonably well – the grasslands are difficult, but the wetlands have come on nicely, there are abundant birds on them. The lake attracts a lot of birdlife in winter too.’

The lake, seen from the hide

We climb the wooden steps to the hide overlooking the lake, and open the long windows to view the birds; the water is blue and scarcely ruffled by the biting wind, the reeds are pale and rustling. There are tufted duck and gadwall on the lake, a coot and a Little Grebe, and Frank is surprised to see that there are now four swans, one of them high up on the bank. ‘We had a big starling roost here a year ago.’ How many birds? ‘About 20, 000 – a good murmuration. But one night the lake froze and they went away the next day – perhaps they know that predators can get at them more easily when it’s frozen. But they’ll probably come back.’

From the hide I also see two humans, cycling along a tarmac-ed strip of runway towards the woodland. The ‘Watchtree Wheelers’, overseen by Ryan Dobson, were set up with £25,000 in Lottery Funding to provide a range of bicycles, tricycles and motorised wheelchair carriers, as well as a hard track around the Reserve,

The Watchtree Wheelers

so that disadvantaged and disabled people might enjoy some ‘quiet recreation’ around the wood; this was the brain-child of another of the Trust’s Directors, Bill Knowles.

The soil

As on my previous visit, the quality of the soil is a topic of conversation. The soil has had a history of disturbance by men with diggers: during the War when the runways were built and in 2001 when the burial chambers were dug.

The clue that it varies from place to place is provided by the vegetation.

We walk down the edge of one of the old runways. The wind-turbines scythe rhythmically overhead. Overburden from the excavation of the burial chambers was laid along the runway and a ‘commercial mix’ of grass was seeded and grew well; but it out-competed the herbs, so Frank brought in haybales from a wildflower meadow and much of the seed they contained ‘took’. ‘It’s now one of our best wildflower meadows,’ he says, and brown hares are frequently seen there. The meadows are grazed in the autumn to stop the build-up of rank grasses – three local farmers bring in cattle and sheep to graze the different areas.

There’s another, newer, wildflower meadow beneath the fourth turbine, sheltered by a hawthorn hedge. ‘It takes time,’ Frank says. ‘It might take 50-60 years for it come right. But I’ve always said we should go for meadows rather than just plant more trees – planting more trees seems to be everyone’s answer these days! Wildflower meadows have been our biggest loss [in the countryside], so if we can make it work, in time it will be really valuable’.

Into the woods

We walk along along another runway, the date ‘28/4/42’ scratched in the cracked concrete, towards the woodlands: two patches of woodland had existed previously, and more than 80,000 trees have been planted to link them, a mixture of Scots pine to encourage the red squirrels, and broad-leaved trees like rowan, hazel, willow and grey poplar. There is a plantation of self-seeded alder, and as we walk along the trail the sunlight picks out the trunks of the birches where brush and saplings have been cut back to create a ‘woodland glade’ effect to encourage butterflies.Great Tits and Coal-tits flitter and chatter amongst the trees.

In one place the Scots pine and other saplings have not grown well: the soil is poor and compacted.

‘The trees will quickly tell you if they don’t like the soil’

‘The killing-sheds were here,’ Frank tells me. ‘The trees will quickly tell you if they don’t like the soil.’

But some of the volunteers have dug holes in the hard pan, and these have filled with water – ‘transitional pools’, Frank calls them, where there are now three species of newt. ‘These areas of different soil, they’re creating structural diversity. We’ve got a range of habitats.’

This is what draws me to Watchtree, not only its size and its range – the mix of woodland, wetland and open water, scrub, wildflower meadow and rubbly, well-drained ground – but the unbounded optimism of Frank and everyone else I meet who is involved with the Reserve. The approach to this site has been empirical, experimental, and – as with all good science – there is a pragmatism and a willingness to understand what is going on, and to either build on the results or take a new approach.

We go through a gate into Pow Wood, where a student is standing by a camera on a tripod, waiting to capture an image of woodland birds. There are huge tree-stumps, draped with sumptuously mossy growth; there are lichens and fungi, and a mix of birch and alder and willow, with a little rowan and oak. ‘The trees were cut down by the Ministry [of Defence] during the war when this was an airfield. All this has regrown naturally.’ Brambles and saplings fill in gaps between the more established trees. ‘The woodlands have got to the stage they need thinning. That’s part of the Management Plan we’ve put forward – the volunteers can do some, but beyond a certain size we need contractors. We’re going to do some training in charcoal burning with the thinner stuff – we’re thinking we could sell the charcoal to our visitors.’

The burial plots

The underground cells are lined up beneath the edges of another runway; although they are covered with vegetation the regularity of their outlines, and the green metal boxes and spinning, shimmering ventilation cowls mark their presence. Ten of the plots have been used over the past 10 years to trial various seed mixes. ‘It’s quite a challenge,’ Frank tells me – just as he told me five years ago. ‘It’s old glacial mineral soil, quite alkaline, pH 7.3. If you try to plough it, you’re turning up rocks and stones. It’s a wet heavy clay mix, and we’re having a problem with rushes starting to take over. About the only thing that will kill them is glyphosate and you have to apply that with dabbers. But we’ve sown a seed mix on them and we get self-heal, knapweed, a variety of grasses.’

Of the hand-planted Devil’s Bit Scabious – several thousand when I was last here – ‘hardly any have survived’, though some have self-seeded and are growing on the stony margins of the runway.

Wildflower plot with scabious, above a burial cell, 2011

Scabious are the food-plant of caterpillars of the Marsh Fritillary butterflies and, although no butterflies have yet established here, Watchtree’s annual Captive Breeding Programme is still ongoing, rearing the caterpillars in cages. The butterflies are then sent out to various donor sites – to Ennerdale as before, where ‘they’re doing well’, and more recently, to nearby Finlandrigg wood.

Where does the funding come from?

Last time I visited, DEFRA’s ten-year funding package was half-way through; it has now ended. This has meant a re-organisation of staffing – former Warden Tim Lawrence has left, leaving one full-time staff member and, for the present, two students working part-time in education and conservation. The Trust’s Directors have been very pro-active in seeking extra funding over the years and currently have a couple of projects proposals under review – a proposal to Cumbria Waste Management and the Community Fund for a compostable toilet at the far end of the reserve, and a large Woodland Management Plan proposal to the Forestry Commission.

At present, the Reserve’s income comes from several sources including the very popular Watchtree Wheelers, membership fees, donations, and the Café. By using volunteers in so much of the conservation work, it has been possible to put some money aside. The day of my visit, a Wednesday, there are two groups of volunteer helpers, with loppers and saws, cutting and laying hawthorn hedges. ‘We still have financial reserves,’ Frank says. ‘We’ve got three or four years to make up the difference between what we spend and what we need to keep going.’ As for the volunteers, ‘They get through an awful lot of work. We’ve got a nice little group at the moment. Mostly retired folk, but we get three or four years’ work out of them!’

As we walk back along the runway towards the smart visitor centre and Café an old tractor approaches and the driver, William Little, stops to chat to Frank. William is a retired local farmer who, as Chairman of Great Orton Parish Council during the Foot-and-Mouth crisis became involved with Watchtree Nature Reserve through the local liaison committee. He, like Frank and some of the other Trustees, has been working for the Reserve since its beginning.

Watchtree Farm, Great Orton airfield, Great Orton burial ground, Watchtree Nature Reserve: it’s a place of such mixed histories. Yet, as on my first visit, I am impressed at the spirit of optimism, of looking to the future, that continues to drive the Nature Reserve forward. It feels a happy place.

Last year it had 16,000 visitors: people coming to enjoy the views, the birds, the flowers, the varied scenery; people coming to use the Wheelers’ facility, to visit the Café, to volunteer; school-parties coming to dip ponds and learn about the countryside that they live in; and on the final Sunday of each month, an increasing number of runners coming to take part in the 5K run.Watchtree has become a symbol of diversification and biodiversity.

As William Little said in a television interview, ‘[The reserve] has turned what could have been a disaster for the local community into an asset’.

Useful information:

The Reserve’s website has lots of information about events, volunteering, Watchtree Wheelers, contact details, map, and more.

A 2001 report on ‘The killing field of Cumbria’ and links to daily reports on the FMD epidemic of 2001

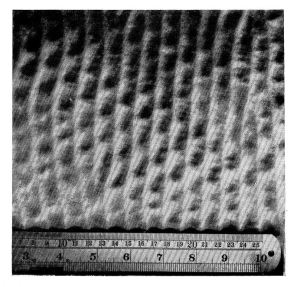

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS) shows the rippled surface of ‘High Dune’, the first Martian sand dune ever studied up close, and part of the ‘Bagnold Dunes’ field. Amazingly, the dunes are actively migrating, at up to about one metre per year.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS) shows the rippled surface of ‘High Dune’, the first Martian sand dune ever studied up close, and part of the ‘Bagnold Dunes’ field. Amazingly, the dunes are actively migrating, at up to about one metre per year.